Language is never neutral. It frames how we perceive civic duty, public policy, and even our behaviour. One word that often slips by unnoticed, yet carries immense weight, is “incentive.” In everyday conversation, we tend to equate incentives with rewards: cash bonuses, gifts, or perks. However, this narrow view obscures the true scope of what an incentive is.

While WordWeb defines an incentive as a “positive motivational influence,” applied fields like public policy adopt a broader interpretation—one that includes both positive and negative motivators. These can range from benefits and conveniences to penalties, restrictions, or the loss of access—tools that raise the cost of inaction and shape decision-making.

In public discourse, especially when discussing democratic governance, it is essential to embrace this wider lens. An incentive, in this context, is any factor, reward or repercussion that influences behaviour. However, there is a fine line between incentive and coercion. Coercion, by nature, often removes meaningful choice by threatening disproportionate consequences.

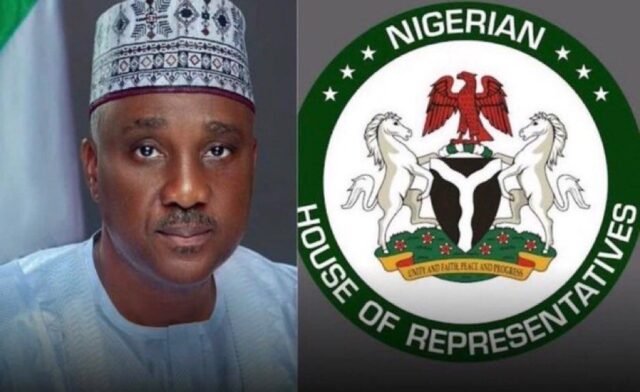

I was reminded of this complexity during a recent online debate about a proposed Nigerian law to make voting compulsory. The bill, sponsored by the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Rt. Hon. Tajudeen Abbas, sparked intense public backlash and has since been withdrawn. It reportedly included fines and even jail terms as enforcement mechanisms. While Mr. Speaker’s proposal aimed to motivate behaviour by raising the cost of inaction, the threat of jail time for abstaining from what should remain a voluntary civic duty does not just blur the line between incentive and coercion—it crosses it.

To be clear, Nigeria’s voter turnout has been declining for two decades. The 2019 general elections saw just 35% of registered voters participate. By 2023, turnout dropped to an alarming 29%, despite a surge in voter registration and youth engagement. This marked the lowest turnout in the country’s democratic history.

This is not merely a civic concern; it is a democratic crisis. While apathy is often blamed, the deeper issues include long-standing distrust in electoral institutions, fears over violence, and logistical frustrations at polling stations. A significant number of citizens feel that elections are either pre-determined or that their votes do not count. Any serious reform must begin by confronting these structural barriers.

In the debate, I argued that public policy should encourage genuine civic participation, not enforce it through coercion. However, critics quickly mischaracterized my stance as advocating for “rewards” for voting, missing the deeper point. The issue is not about handing out gifts; it is about how governments design incentives to influence behavior by altering the cost–benefit analysis that individuals perform.

Take the example of a salary increase. To an employee, it might feel like a reward for hard work. However, to an employer, it is a strategic incentive, a tool to boost morale, enhance productivity, and reduce turnover. The framing may differ, but the function is the same: to steer behaviour toward a desired outcome.

Likewise, non-monetary incentives, like flexible work hours, public recognition, or even social pressure, can be just as powerful. The key is not whether an action feels like a “reward” or a “punishment,” but whether it effectively shifts behaviour in a way that is sustainable and ethical.

In the realm of public policy, the nuance of incentives becomes even more critical. When the Nigerian government implemented the Bank Verification Number (BVN) and National Identification Number (NIN) systems, initial uptake was sluggish. But once registration became a precondition for accessing essential banking and telecommunications services, compliance surged. This is a textbook example of nudge theory, popularised by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, which argues that subtle changes in the “choice architecture” can influence behaviour without restricting freedom of choice. In this case, the incentive was not a gift; it was the practical reality of making vital services accessible only to those who registered.

Research in political psychology suggests that coercive interventions may undermine intrinsic motivation over time. A 2019 study in Political Science Research and Methods found that extrinsic motivators, such as electoral pressure, can crowd out intrinsic motivations in political behaviour. While people may comply with rules to avoid punishment, this approach risks transforming civic participation from a voluntary act into a transactional response driven by fear. Over time, such policies may secure short-term compliance at the cost of eroding public trust and intrinsic engagement in democratic processes.

Globally, we see similar patterns at work. In the United Kingdom, digital tax filing has become the norm not because citizens are rewarded for using the system, but because it offers unparalleled convenience. Likewise, traffic regulations in Britain are obeyed not due to public accolades but to avoid predictable, tangible penalties such as fines, penalty points, and increased insurance premiums. These are incentives at work, positive and negative, steering behaviour by making the alternative less attractive.

Cultural context, however, matters. Policies that work seamlessly in one society can falter in another if they do not align with local trust dynamics, civic values, and social norms. In Australia, where voting is compulsory and enforced with a modest fine, high turnout is maintained partly because of a strong underlying sense of civic duty. The Australian Electoral Commission even frames voting as a civic duty comparable to paying taxes or serving on a jury. In contrast, Sweden enjoys robust voter participation, often exceeding 80%, without any legal compulsion, thanks to high institutional trust and a deeply rooted culture of collective responsibility.

In Nigeria, however, the situation is more delicate. A 2020 Afrobarometer survey revealed that while many Nigerians cherish their voting rights, overt coercion breeds resentment. Heavy-handed measures risk being perceived not as efforts to serve the public interest but as instruments of elite control, diminishing the intrinsic motivation to participate in civic life.

The misunderstanding of incentives can lead to serious policy missteps. When motivation is misconstrued as something to be enforced solely through punitive measures or superficial “rewards,” the opportunity to design empowering, trust-building systems is lost. Smart policy should not seek obedience through fear; it should earn participation through trust.

Instead of imposing jail terms for non-compliance, Nigerian policymakers could implement reforms that address the real barriers to participation—such as expanding early voting, improving transparency in result collation, reducing queuing time through better staffing and logistics, or even allowing diaspora voting. Each of these is a behavioural nudge, a subtle shift that makes the right choice the easier one.

Ultimately, incentives are about understanding human behaviourand crafting policies that align public interest with personal motivation. When designed thoughtfully, incentives do not feel like manipulation; they feel like common sense. The real challenge is to build a system where the right action becomes the simplest, most compelling choice, one that fosters lasting engagement rather than merely securing short-term compliance through fear.